The influx of Chinese dealers turned Sandakan into a blooming trade town. Until the Japanese invaded and forced thousands to work and die for them.

Situated at the east coast of Sabah, Sandakan was found by Scottish arms smuggler William Clark Cowie, where he set-up the first European settlement there. Many names were considered and cycled throughout the years, but it eventually was coined in Sulu language as “Sandakan”, meaning the place that was pawned.

Previously under the control of the Sulu Sultanate during the 1700s, they sold their land away for reasons unknown. But the first British resident of Sandakan, Willian B Pryer, took control of the administration, and established law and order for residents and incoming traders, which led to Sandakan being nicknamed “little Hong Kong”.

The birthplace of “little Hong Kong” in Malaysia

The origin starts off when Sandakan was made capital of North Borneo in 1884, turning Sandakan into a flourishing commercial port for early settlers.

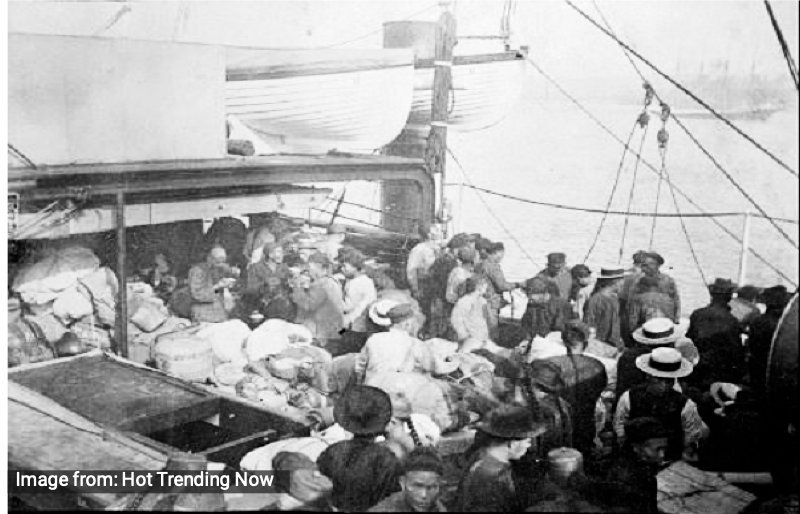

The Chinese began entering Sabah in larger numbers only after 1881, because the British North Borneo Company (BNBC) managed this newly established town, and required a sizable population to supply labour to aid development.

The BNBC wanted to strategically encourage the Chinese from Hong Kong to plant their roots in Sandakan, in hopes to economically develop the mushrooming settlement. To achieve their objective, the BNBC came up with three main immigration schemes.

In one of the schemes, the BNBC decided to offer free passage to Hong Kong residents who wanted to migrate to Sabah. Gradually in batches, the plan effectively brought in at least 1000 Chinese immigrants. This was a jump start to their following schemes.

Successful pioneers of the previous immigration scheme were sent back to Hong Kong to encourage them to migrate to Sabah. This worked out well, and Sandakan eventually was made up of one fifth of Chinese people, with well over 30,000 Chinese.

But the BNBC decided they needed more, so they also came up with a free passage “pass” for those with a sizable land to invite any of their bona fide Chinese relatives to settle in Sandakan.

The challenges of trading and migrating to Sandakan

Although well populated and self-sustaining, Sandakan still faced heavy competition from more developed ports in Malaya, especially Singapore and Labuan. Moreover, the new migrants were city-folk, and were unaccustomed to the jungles surrounding Sandakan. They eventually moved to Singapore or Labuan to seek a more urbanised lifestyle.

Another challenge they faced was giving a fix salary every month to Chinese labourers. Because this turned them into unproductive workers who only worked for bare minimum rather than profit.

Nevertheless, the establishment did not lose all its migrants and still attracted traders from Hong Kong and Singapore. Hence why most who reside there now could speak the Cantonese and Hakka dialect fluently, giving the town a vibrant multicultural atmosphere.

But that all took a heavy downturn when World War II begun.

The beginning of thousands of deaths

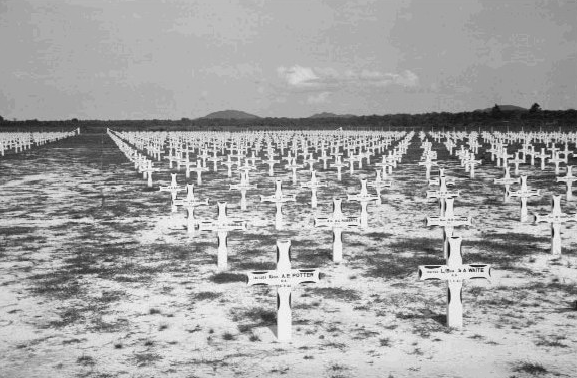

Every 25 April, a public holiday in Australia and New Zealand called ANZAC Day (Australia and New Zealand Army Corps) is held to commemorate all fallen soldiers and veterans during World War II.

Although Malaysians do not share this holiday, it’s infamously related to an event that happened between the roads of Sandakan and Ranau. The east coast town of Sandakan also holds a memorial service in Sandakan Memorial Park to remember the same ANZAC Corps of almost 1,900 prisoners of war.

As the prosperity of Sandakan plummet when World War II began, the Japanese Occupation arrived in Sandakan shores on 19 January 1942, and the war’s outbreak invited bombers from Allied Forces that nearly destroyed the whole town.

They were met with resistance at first, but the Allied forces soldiers were defeated and used as slaves. At the height of it, there were 1,500 Australians and 770 British soldiers captured.

The Japanese soldiers forced these strategically malnourished prisoners of war to build an airport on top of Sandakan. But that didn’t last very long because their efforts were destroyed by another Allied forces attacks mid-construction. Since there was nothing else left in Sandakan, they were forced to relocate.

The unintended path for the war prisoners

Initially, their plan was to get the prisoners to walk all the way to Jesselton (now known as Kota Kinabalu). Since the Japanese were unfamiliar with Sabah’s terrain, a local was assigned to carve out their pathway.

But little did they know, the pathfinder chose the roughest parts of the jungle to cross.

The plan backfired massively when the local pathfinder was unaware the path was to be travelled by the prisoners of war as well. The path is said to be 192 kilometres long, while the prisoners were abused, starved, and forced to carry equipment for the Japanese along the way.

Although their final destination was Jesselton, the Japanese were forced to stop and settle in Ranau, because the pathway was too gruesome to trek, even for the Japanese. As a result of this terrible journey, only 6 out of 1900 prisoners survived or escaped along the long harsh trail.

only 6 out of 1900 prisoners survived or escaped along the long harsh trail.

The event was infamously termed as the “Sandakan Death March”. Now, their deaths are part of Sandakan history. It’s even being turned into a tourist attraction, where expert jungle trekkers guide tourist along the path of the Death March.

When the Japanese surrendered and left Sandakan on 19 October 1945, only then the war-torn town got a chance to gradually repopulate and rebuild. BNBC returned to control after to assist their re-development.

Unfortunately, after looking at the unrepairable destruction left by the Japanese, the BNBC decided to relocate their administrative capital to Jesselton. But insisted to develop Sandakan’s fishing industry, which similarly attracted Hong Kong fishermen and traders as before.

Sandakan death march history might have forgotten, but history never leave without a trace. Little Hong Kong might not be the name it was known for to this day, the same cultural atmosphere as it was during its establishing prime was very much alive.